A small glimmering green insect, the Emerald Ash Borer, has found its way into Boston’s forest.

Often shortened to EAB, this beetle feasts on ash trees, the 6th most common street tree in Boston. Of the approximately 38,000 street trees across the city, 1,817 are green ash trees (Fraxinus pennsylvanica) and make up 4.7% of Boston’s street tree population, as well as an untold number of park trees and trees on private property.

It’s not the insect itself that causes harm, but rather the larvae. The beetle lays its eggs in the grooves of the bark on ash trees and the emerging larvae then feed on the tree’s living cambium tissue, resulting in foliage loss, a decline in health, and ultimately the death of the tree.

Image of a mature Emerald Ash Borer photographed by Leah Bauer, USDA FS Northern Research Station, Bugwood.org.

EAB arrived in the United States in 2002 from Asia, likely in packing material made of wood. Unfortunately, with no natural predators in the U.S., EAB has proliferated across the country. In Michigan alone, it has been estimated to have killed 40 million trees. About a decade ago EAB was found in Boston’s Arnold Arboretum. It has since spread throughout the city and is infecting the city’s ash tree population.

To control the spread of EAB and prolong the lives of ash trees, Boston’s Urban Forestry division has begun treating these public trees across the city of Boston, by injecting an insecticide, emamectin-benzoate, into the tree. This insecticide interrupts the insect’s life cycle by killing the larvae under the bark and does not harm the tree. After completing its street tree inventory in 2021, the City of Boston identified 1,165 public ash trees in good condition for treatment. Each injection can protect a tree for 2-3 years. Only trees with more than 50% of their canopy remaining are likely to respond successfully to injections.

Todd Mistor, Boston’s Director of Urban Forestry, has emphasized that this effort is “about [the] preservation of a diverse tree canopy.” Although the city is no longer planting ash trees, it is “committed to continuing this project in the future” and to preserving as many ash trees as it can. Only time will tell how well the insecticide performs in Boston, but Mistor is hopeful that these injections will stem the loss of ash trees and slow the spread of EAB.

Unfortunately, it is not always possible to detect the insect in time to intervene. Sometimes an ash tree has already been severely harmed by the EAB and cannot be saved with injections. In these cases, these ash trees are removed. They not only present a safety hazard to the public, but they also serve as breeding grounds for EAB, furthering the infestation of the beetle to new ash trees. Though unfortunate, these removals create opportunities to replant with other species to increase the diversity of trees that make up Boston’s urban tree canopy.

The city’s new approach is in line with its new Urban Forest Plan, released last year. The plan called for additional funds for long term tree care. “It’s exciting to see the city take a proactive approach to preserving these ash trees with systemic, targeted insecticide injections,” said Claire Corcoran, staff arborist at Speak for the Trees. “Many of these ash trees were planted decades ago in rows along specific streets; their loss would have left many streets with little to no tree canopy.”

What you can do

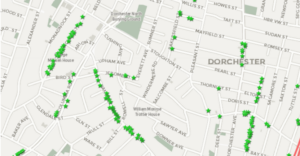

Residents can help in controlling the spread of EAB. The City of Boston has created a map of all public ash trees, and will soon feature a layer that will identify the ash trees that have been treated. To identify if a tree is infested, look for D-shape exit holes in the bark, “blonding” from woodpecker feeding, dieback in the upper third of the tree canopy, and sprouting at the base of the trunk. If a tree is more than a third dead, it needs to be removed for public safety. The City of Boston replants street trees annually in the fall and spring through their street tree planting program. If you suspect a city tree has EAB or if you would like to request a replacement tree, call 3-1-1 or visit the city’s 311 request page.

Image of the D-shaped exit holes left behind by mature Emerald Ash Borers emerging from trees. Photo captured by Daniel Herms of Ohio State University, Bugwood.org.

Image of “blonding” on a tree that is a result woodpeckers over feeding on the abundance of Emerald Ash Borer larvae. Image sourced from the University of Delaware CANR News Article.

Additional information can be found on the city website, as well as the State Urban Forestry website and the US Forest Service. If you have an ash tree on your property, please keep an eye out for EAB and its tell-tale signs and call a local arborist with any questions. Stay tuned for an upcoming blog post about EAB on private property.

Keep an eye out for future tree giveaway dates on our events calendar, social media channels as well as in our bi-weekly newsletter.